[NOTE: REFERENCES AT BOTTOM IN ITALICS POSSIBLY CAME FROM MY BLOG. REFERENCES AT BOTTOM IN BOLD DEFINITELY CAME FROM MY BLOG]

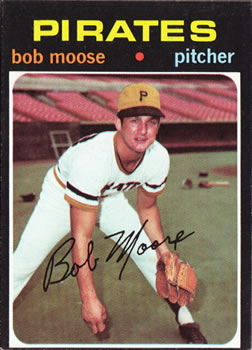

In 10 seasons (1967-76), all with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Bob Moose pitched in 289 games, winning 76 and losing 71 with a 3.50 ERA. But the real story of Bob Moose is full of what-ifs and a tragic ending. Did the recklessness that killed him in an October 1976 auto accident derail what might have been a stellar baseball career? Did his fun-loving nature that endeared him to others make him lose focus? The repeated pattern of brilliance followed by mediocrity and worse suggests that.

In 10 seasons (1967-76), all with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Bob Moose pitched in 289 games, winning 76 and losing 71 with a 3.50 ERA. But the real story of Bob Moose is full of what-ifs and a tragic ending. Did the recklessness that killed him in an October 1976 auto accident derail what might have been a stellar baseball career? Did his fun-loving nature that endeared him to others make him lose focus? The repeated pattern of brilliance followed by mediocrity and worse suggests that.Robert Ralph Moose Jr., son of Molly and Robert Moose Sr., was born and raised in the small western Pennsylvania town of Export.1 Moose, born on October 9, 1947, was partially of Italian descent; his mother was a homemaker and his father drove a Pittsburgh bus. He had a sister named Debbie.

Moose played six years of Little League, showing at an early age that he was special. His mother said, “When Bobby was growing up, we attended all his games. We never went on vacation because Bobby would be playing ball.” In four years of baseball at Franklin Regional High School, Moose tossed three no-hitters and lost only two games. Also a star football and basketball player, he is regarded as the best athlete in his school’s history.2

Less than a week after graduating from high school in 1965, Moose became a professional. He joined the Pittsburgh Pirates farm system team in Salem, Virginia. In three minor league seasons (playing for Salem, Virginia; Gastonia and Raleigh, North Carolina; Columbus, Ohio; and Macon, Georgia), he compiled a 29-10 pitching record.3 Based on that performance, the Pirates called him up toward the end of the 1967 season. He made his major league debut on September 19, 1967, and the Houston Astros roughed him up in the Astrodome. Ten days later, pitching at home in Forbes Field, he got revenge by pitching a complete game victory over the Astros.4 He was 19 years old.

The next year, after pitching well in spring training, Moose made the Pirates’ Opening Day roster. In 1968, his first seven games were all in relief. He saved three of them but blew one save and took a loss. On May 9, he made the second start of his career, giving up two runs in six innings and taking the loss. Eight more relief appearances followed. Despite lowering his ERA from 4.02 to 3.24, he picked up two more losses. On June 9, he started and allowed just one run over 8 1/3 innings, picking up his first win of the season. The Pirates were pleased with that effort and put him into the starting rotation. In his next start, on June 14 (his second-ever at Forbes Field), Moose pitched 7 2/3 innings of no-hit ball before surrendering a hit. He finished with a two-hit shutout. He continued his dominant pitching with another two-hit shutout and at the end of June his record stood at 3-5 with an ERA of 2.51.

July was a hard luck month for Moose. He maintained his low ERA, but ended the month with a season record of 4-8. The only win in July was another shutout. Through his first 12 starts of 1968, the Pirates had not scored more than three runs. Fortunately his luck turned a little brighter in August. In four starts, he won two and lost one. But tough luck returned in September with two wins and three losses, bringing his final tally to 8-12.

Yet Bob Moose projected much promise for 1969. In 170 2/3 innings, he had a 2.74 ERA, allowing a little over seven hits and two walks per nine innings. He was chosen as Pirates Rookie of the Year for 1968.5 The stocky, 5-foot-11 pitcher with a chaw of tobacco in his mouth was on his way. Showing how life was very different for players before the free-agency era, Moose sold cars in the off-season.6

Moose came charging out of the gate in 1969. His first two starts were complete-game victories. Not normally a strikeout pitcher, he tallied 20 Ks in the two games. After his fifth start in early May, he was 3-1 with a 3.60 ERA. Then things slowed down. Over the next three weeks he started only two games and relieved in three. Back in the starting rotation in late May, he picked up two wins, including another complete game effort. However, he was soon returned to the bullpen, becoming a well-used reliever. Between late June and mid-August he made 18 straight relief appearances, picking up three saves and one win.

When the Pirates gave Moose another chance at starting, he made the best of it. In the final six weeks of the season, he made nine starts, winning seven and pitching three complete games. One game was especially memorable. Facing the New York Mets in the middle of their legendary World Series drive, amid a pennant race, the 21-year-old pitcher no-hit them at Shea Stadium.

A week later, he pitched in relief and picked up his fourth save of the season. Five days later he pitched a complete-game victory. In three late-season starts he fanned 10 or more batters, including 14 in the start before the no-hitter. Pitcher of the Month awards didn’t exist in 1969; if they did, Bob Moose would likely have won it for September. That month he was 5-1, with three complete games, including the no-hitter, as well as the save. Moose finished the year with a 14-3 record, averaging a strikeout an inning while limiting hitters to 7.9 hits per nine innings. He carried a team-low 2.91 ERA for starters and his .824 winning percentage was the highest in the league. Showing the team he was versatile, he started 19 games and relieved in 25. If he had been strictly a starter he might have been a 20-game winner.

Before Bob Moose turned 22, he set two records that still stand: most strikeouts (14) in a game by a Pirates right-hander and the youngest pitcher to throw the most no-hit innings in a game at two major league parks. No pitcher went further with a no-hitter in the more than 4,600 games played between 1909 and 1970 at Forbes Field.7 Jim Bunning’s perfect game was the only other no-hitter ever pitched at Shea Stadium.

Unfortunately the trajectory set at the end of 1969 did not continue in 1970. Moose was kept out of baseball action by Marine Corps reserve duty, and didn’t make his first 1970 start until the Pirates’ 14th game. After three starts, he was 0-3 with an 11.30 ERA. But he got it together, winning six of nine decisions and pitching at least eight innings in eight of the nine starts. More importantly, he reduced his ERA to 3.96. On June 28, he pitched four-hit ball over seven innings and didn’t pitch again in over a month.

Sadly, he suffered elbow pain just when he had been pitching well.8 It was a bad omen for a young pitcher. He did return to the rotation and started six games in both August and September, finishing the season with an 11-10 mark. His other numbers raised some concern though. In his first two seasons he gave up 7.7 hits per 9 innings. In 1970 he gave up a hit an inning. His strikeouts dropped off as well, going from 7.7 per nine innings to 5.6 per nine innings. In addition, his 3.98 ERA was more than a run a game higher than his previous two year totals. His career was going in the wrong direction. But the team was going in the right way in 1970. The Pirates made the postseason for the first time since 1960. In the three-game National League Championship Series sweep by the Cincinnati Reds, Moose pitched the final game and took a hard-luck loss, going 7 2/3 innings, while allowing only four hits and three runs.

One thing that didn’t help Moose’s consistency was fulfilling his Marine Corps Reserve commitment.9 He hade to leave the Pirates for a couple of weeks every season and also had some weekend duty. Undoubtedly this had something to do with being shuttled between starting and relieving. But being an able-bodied male, it beat the alternative of going to Vietnam.

The pattern of starting and relieving resurfaced in 1971. After four starts, he relieved twice, then started nine games between mid-May and early July. In those nine starts he pitched three complete games including a three-hit shutout, but also lasted three innings or less in two of the games. Inconsistency was becoming his middle name.

He started five games between late July and late August and only got past the fifth inning once. By September he pitched only out of the bullpen. A decent 11-7 record covered up what otherwise was his worst pitching season. He gave up almost 11 hits every nine innings, only struck out a batter every other inning, and his ERA was 4.11.

But the Pirates won it all in 1971, defeating the San Francisco Giants three games to one in the National League Championship Series and overcoming the powerful Baltimore Orioles four games to three in a dramatic World Series comeback. Moose pitched in middle relief in one game of the NLCS, middle relief in the first two World Series games against Baltimore, and started Game Six, going five innings. In all four games he had no decisions. Still, being a World Series champion days after turning 24 had to be sweet. Just after Game Seven, Bob Moose played a central role in a unique championship celebration. Still wearing his champagne-stained uniform, he was whisked away to a waiting helicopter to serve as best man at the wedding of teammate Bruce Kison (winner of Game Four).10

But when the World Champion Pirates prepared to defend their title in 1972, Moose did not start out well, going 0-2 with a 7.32 ERA in his first three starts. Once again he was sent to the bullpen. Then he pitched 11 innings in his next start and followed that with a four-hit shutout. Two starts past the eighth inning coupled with another complete game cemented him in the starting rotation. By mid-June he was riding a five-game winning streak and had lowered his ERA to 3.31.

But then the inconsistency that followed him returned. Over seven starts he failed to pitch into the eighth inning and went on a four-game losing run. Seemingly out of nowhere he pitched two consecutive shutouts and a seven-inning winning effort to bring his season totals to 9-6. The rest of the way he took his turn in the rotation, finishing the season with a 13-10 mark, a 2.91 ERA, and a career-high 226 innings pitched. Always a pitcher with good control, Moose gave up less than two walks per nine innings. For the third year in a row, the Pirates made it into the postseason. After they won National League Championship Series Game One against the Reds, manager Bill Virdon gave Moose the ball for Game Two. But Moose pitched the worst game of his career, not retiring a batter.

The next time he got the ball it was even worse. Coming into a tie game in the bottom of the ninth of the deciding game, Moose uncorked a wild pitch, allowing George Foster to score the pennant-winning run. This was a very tough end to what otherwise was a good season.

Still only 25 years old, Bob Moose began his seventh major league season in 1973 with a four-hit shutout of the Cubs. That put much-needed distance from the previous fall’s nightmare postseason. He won his next start, but his performance took another dive and by late May he carried a 3-4 record and a 3.95 ERA. He pitched two complete games and won two of three decisions, but then he lost two straight in mediocre efforts, only to come out of it with a shutout of the Expos at the end of June. This alternation of brilliance and mediocrity is hard to fathom.

It was said Moose liked to have a good time.11 He may have let that affect his pitching. He really seemed to concentrate and bear down only when things were going badly. However, once he righted his ship, he seemed to let up. After the shutout, he went 0-3 over his next five starts and in four of the starts he failed to pitch more than four innings. His ERA also rose to more than four. Once again he turned things around, winning five of six decisions, lowering his ERA to 3.55, while squaring his record at 11-11. Unfortunately Moose’s season again ended on a bad note. He was removed from the rotation and pitched in relief the last week of the season. His season totals were 12 wins, 13 losses, with a decent 3.53 ERA, but he gave up more than a hit an inning and struck out only 5.5 batters per nine innings.

Something was clearly wrong with Bob Moose once the 1974 season began. He didn’t have his stuff and it showed quickly. Through six starts and one relief appearance, he was 1-5 with an ERA of 7.57. He displayed abnormal swelling and discoloration in his pitching arm. In late May, a blood clot was found in his shoulder. Emergency surgery removed the clot, along with one rib.12 After the surgery he was told he would never pitch again. He didn’t pitch again in 1974 but vowed to be back next year, showing the bulldog-like determination that his teammates admired.

Hard work and self-confidence paid off for Bob Moose in 1975. His belief in himself came out in spring training in Bradenton, Florida when he told a reporter, “I feel like I have a new lease on life. I’m throwing as well as I ever did. In fact, I think I’ll be a better pitcher.”13 He showed the Pirates he was ready to pitch in the big leagues again and he made the Opening Day roster. He started the fourth game of the season, but lasted less than four innings and took the loss. Over the next five weeks he pitched out of the bullpen with reasonable success. He got back into a starting role in late May and pitched eight innings, allowing three earned runs. However, in his next start he lasted only four innings and allowed six runs. He was sent back to the pen and uneven success.

At the end of June he was 0-2 with a 5.88 ERA. He didn’t pitch in July or August because of a badly torn thumbnail on his pitching hand. Maybe he was trying too hard. When he returned in September, it was in relief. He tossed a 7 1/3 inning effort, picking up his first win of the season. Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh said: “That’s as good as I’ve seen him in a couple of years. He had a heck of a breaking ball and when he had to reach back, it was fast.”14 That earned Moose a start in late September, and he made the best of it in a complete-game three-hitter against the Phillies. It was the last game he pitched in 1975. It did even his record at 2-2, while lowering his ERA to 3.72. The Pirates got into the NLCS again but lost three straight games to the Big Red Machine. Though Moose did not pitch, he still ended the regular season on a very positive note.

1976 was a turning point season for Bob Moose. For the first time since his rookie year he began the season as a relief pitcher, and that seemed to agree with him. In his first 13 games, over more than 23 innings, he was unscored upon. In those games he had six saves and was 1-0. He finally surrendered some runs but still pitched very well. On June 18, his record was 3-1 with eight saves, along with a 1.09 ERA. Over the next three weeks Moose wobbled some, losing three games. But on July 7 he picked up his 10th save and was the team’s established closer, carrying a good 2.16 ERA.

The Pirates lost the next five games and Moose made it six in row with his first start of the season. He lasted 5 2/3 innings and gave up six runs. In his mind he obviously still believed he was a starter. He followed this poor start with a blown save and another loss. At the end of July he was 3-6 with a 3.04 ERA. Over the last two months of the season, he started one more game and lost it; he relieved in 15 games, picking up two losses and no saves. He finished with a 3-9 record and a fair 3.70 ERA. Once again he flashed brilliance but could not maintain it. He finished the season badly, yet his 10 saves led the Pirates in 1976. He might have been the closer for the Pirates the next year.

Just after the 1976 season ended, on October 9, Pirate Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski held a party for Pirate players at his golf course in eastern Ohio. On the way to the party Bob Moose lost control of his Corvette and ran into an oncoming car. Police reports of the accident said Moose was driving too fast for the rainy conditions.15 Two young women in the car with Moose were injured and two people in the other car had slight injuries. Bob Moose wasn’t that lucky. He died at the scene.16 It was his 29th birthday.

Moose left his high school sweetheart a widow with a four-year-old daughter, April. There were rumors that he was not always faithful to his wife Alberta, and the presence of the two young women in the car when he was killed fueled that talk. If the rumors were well-founded, his behavior would certainly not be unique among Pirate players specifically, or professional athletes generically.17

There was no question, however, that Moose was anything but a real competitor. Pete Rose said, “Bob Moose was my kind of player. He would fight you to the bitter end.”18 One has to wonder if he was trying too hard when he lost big parts of the 1974 and 1975 seasons to injury.

The funeral was held at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Export. Moose was a popular player with his teammates and many current and former players were in attendance. No one better displayed the fondness his teammates had for him than Dock Ellis. Ellis, who had pitched an American League Championship Series playoff game for the Yankees the night before the funeral, took a flight to Pittsburgh, chartered a helicopter to Export, and arrived just in time for the service. Willie Stargell was too overcome with grief to deliver a eulogy.19 Bob Moose was laid to rest at Twin Valley Memorial Park in Delmont, Pennsylvania.

A plaque was dedicated to Moose in the Pirates locker room at Three Rivers Stadium. It read, “A great competitor who had desire, confidence, class and style, but above all, the ability to be color blind when it came to people from origins other than his own.”20 At a time when a good number of Pittsburgh fans (who were mostly white) had issues with the number of black and Hispanic players on the team, local boy Bob Moose showed a better way.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by David Lippman and Rory Costello, and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Bob Moose was the second major leaguer to come from Export– named because it was the first place in the area to export coal. The other was Jimmy Ripple, who played the outfield for the New York Giants, Brooklyn Dodgers, Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Athletics in the 1930s and 1940s.

2 Bob Cupp, “Memories of Moose,” Pittsburgh Tribune Review, April 27, 2007.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Pittsburgh Pirates 1969 yearbook.

7 Pittsburgh Pirates Official Scorebook, 1971.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Pittsburgh Pirates Official Scorebook, 1972

11 Cupp, “Memories of Moose.”

12 Charlie Feeney, “Moose has Surgery for Arm Clot,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 31, 1974

13 Bob Smizik, “Moose Pirate Confidence Man,” Pittsburgh Press, March 21,1975

14 Bob Smizik, “Moose Answers Call and Rescues Career,” Pittsburgh Press, September 13, 1975

15 “Bob Moose, Pirates Pitcher Killed in Auto Crash,” Associated Press, October 10, 1976.

16 Ibid.

17 Bob Adelman and Susan Hall, Out of Left Field, Willie Stargell and the Pittsburgh Pirates. Two Continents Publishing Group, 1976. This book shows the promiscuity of Pirate players when Bob Moose was on the team.

18 “Bob Moose, Pirates Pitcher Killed in Auto Crash.”

19 “Former Teammates, Fans Attend Funeral for Pittsburgh’s Moose,” United Press International, October 14, 1976.

20 David Nightingale, “The Pirate Problem,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1985.

No comments:

Post a Comment